Japanese Red Cinema: Koji Wakamatsu & Masao Adachi | Offscreen

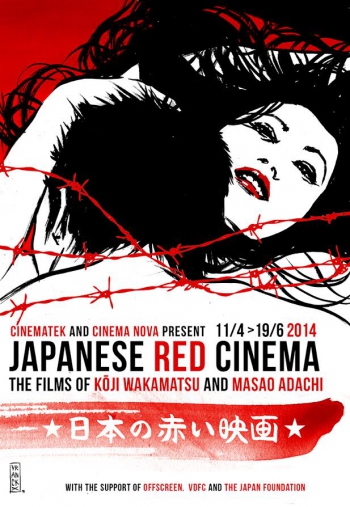

JAPANESE RED CINEMA: KOJI WAKAMATSU & MASAO ADACHI

Japan in the 60’s was a place marked by violent protest movements: opposition against the post-war politics grew even more, and a new left made up of various anti-establishment groups was born. The renewal in 1960 of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (known as Anpo) is seen by many as a new step of American neocolonialism in Japan, as well as the latter’s entrance into the imperialist mindset of the US and its ultimate transformation into a military base during the Vietnam war. This event catalyses a social struggle, and the flames of dissent are fanned once Anpo is to be extended at the end of the decade: clashes with the police and extreme right groups are rife, and armed revolutionary groups emerge to radicalise the effort.

The revolution in also present in cultural circles through a wave of artistic movements deeply rooted in the social climate which explore new territories and break free of the mould. In the film world, this meant a questioning of the rigid system put in place by the major studios. Alternatives arise and with them a new generation of filmmakers who innovated not only through socially- conscious documentaries but also in the field of erotic cinema. The combination of oftentimes violent social tension and freedom of experimentation bred a dynamic form of cinema, marked by its times but still wholly relevant today. Cinema Nova will be exploring this period through the lens of a chief figure of those movements, Masao Adachi, in conjunction with a restrospective of the works of Koji Wakamatsu at Cinematek.

MASAO ADACHI

Author, critic, theorist, screenwriter, actor and director, Masao Adachi is a freeform artist whose work has served the purpose of creative research as well as political action, which has resulted in several decades spent in hiding followed by a stint in prison. His spirit of independence and radicalism contributed to his falling off the Japanese cinema radar until recently. As the works of his contemporary Wakamatsu were internationally restored, Adachi’s name has logically resurfaced and his oeuvre finally recognised.

Adachi is a man of his times, incarnating the revolutionary avant-garde spirit of the political and artistic context that formed him. He studied cinema and directed his first movies through experimental collectives that he himself started. He also became political during the student protests and saw in the film medium a weapon of social upheaval. In 1966 he became acquainted with Wakamatsu, with whom he collaborated extensively through the years, and also took part in some of Ôshima’s films. In 1974, after having travelled through Palestine with Wakamatsu, Adachi decided to extend the film revolution into the armed revolution and left Japan in order to join the Palestinian cause as a member of the Japanese Red Army. He lived in clandestine hiding until his arrest in Beirut in 1997 and spent 18 months in prison until his extradition to Japan. He now lives in Tokyo and can never leave the country. In 2006 he directed a film inspired by his experiences and has most recently collaborated with French artist and filmmaker Eric Baudelaire.

MASAO ADACHI & KOJI WAKAMATSU

In 1966, Masao Adachi crossed paths with Kôji Wakamatsu, a young filmmaker who had already made a name for himself with his self-produced challenging erotic films, thanks to his aesthetic prowess and noteworthy productivity - at times churning out close to 10 films a year- as well as a diplomatic scandal which added a tinge of notoriety to his reputation. Adachi was drawn to the rebellious yet accessible potential of the Pink genre, through which subversion is achieved by using nudity to subtly dissimulate a larger political message. While Wakamatsu was already exploiting the concept, his collaboration with Adachi managed to deepen his political engagement. United by their unruly anti-establishment rules, Wakamatsu and Adachi complemented each other to perfection and lived the revolution in their respective manner: Wakamatsu with the idea that film was a way to "kill cops without going to prison", and Adachi deciding that there was no need to choose between a gun and a camera when you have two hands at your disposal.

The Ugly One

Following his first meeting with Masao Adachi, Eric Baudelaire takes on a new creative challenge, responding to Adachi’s desire to return to Lebanon without the possibility of physically carrying out his wish. In a unique take on the process of filmmaking, the directors produce a film essay about commitment and life, including romantic life, within the revolutionary factions.

The Ugly One

Following his first meeting with Masao Adachi, Eric Baudelaire takes on a new creative challenge, responding to Adachi’s desire to return to Lebanon without the possibility of physically carrying out his wish. In a unique take on the process of filmmaking, the directors produce a film essay about commitment and life, including romantic life, within the revolutionary factions.

The Ugly One

Following his first meeting with Masao Adachi, Eric Baudelaire takes on a new creative challenge, responding to Adachi’s desire to return to Lebanon without the possibility of physically carrying out his wish. In a unique take on the process of filmmaking, the directors produce a film essay about commitment and life, including romantic life, within the revolutionary factions.

The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu

Fusako Shigenobu left Japan in 1971 to found the Japanese Red Army - a terrorist fringe group dedicated to supporting the Palestinian cause - and lived in Lebanon for 30 years. During Adachi’s own exile in Beirut, he met Shigenobu, and bonded with her not only over the experience of being far from home, but also over their shared fate of coming back to Japan without the possibility of ever being able to leave.

The Ugly One

Following his first meeting with Masao Adachi, Eric Baudelaire takes on a new creative challenge, responding to Adachi’s desire to return to Lebanon without the possibility of physically carrying out his wish. In a unique take on the process of filmmaking, the directors produce a film essay about commitment and life, including romantic life, within the revolutionary factions.

Sex Jack

Like many other films of the period, "Sex Jack" opens with images of anti-Anpo protests. Filmed in black and white by Wakamatsu, the film follows a defeated militant group whose hideout has been discovered by the police, resulting in the arrest of their leader. A mysterious young thief helps them escape.

Conference: The cinema of Masao Adachi & Kôji Wakamatsu

Cinema Nova, in collaboration with the Cinematek, welcomes two Japanese cinema specialists to a conference on Masao Adachi and Koji Wakamatsu, with the participation of Masao Adachi from Japan. Free entrance.

Red Army-PFLP: Declaration of World War

After visiting Palestinian camps in Lebanon and Jordan and spending time with Arab revolutionaries, Wakamatsu and Adachi test the "landscape theory" in foreign lands. The images filmed there will be Adachi’s basis for a radical film manifesto against disinformation, a propaganda tool for world revolution and a rare document which shows the battle from within its ranks.

Secrets behind the Wall

Japan, 1960. In a housing complex, a young introverted student observes his neighbors through a telescope. The voyeurism of a young man isolated and gloomy, will cause an explosion of madness.

Ecstasy of the Angels

In "Ecstasy of Angels", a revolutionary organisation (inspired by Auguste Blanqui’s "Société de saisons") is mired by internal turmoil, betrayal and ambient paranoia. "Ecstasy..." is a cocktail of revolt, sex, violence and dialectics, often simultaneously, in Wakamatsu’s incomparable style.

A.K.A. Serial Killer

A film-essay based on a news item wherein 19 year-old Norio Nagayama murders four people without any apparent motive, Adachi and his fellow filmmakers build this story around the "landscape theory", which posits that all landscapes are fundamentally linked to a figure of power, rendering Japan a toxic place that can drive sane men to madness.

The Embryo Hunts in Secret

A shop manager tries to make an obedient slave out of one of his employees and keeps her locked up in an appartement. An infernal "huis-clos", shot in five days in a minimalistic style. Freudian neuroses, violence and scenes of disturbed sexuality proved too much for the censors at the time of its release.

Three resurrected Drunkards

Three young Japanese men freshly out of school go for a swim at the beach and discover in amused bewilderment that their clothes have been exchanged for Korean tunics. They pursue their adventures wearing their new costume, with two bloodthirsty Koreans at their heels. With this film, Ôshima reveals his concern over the discrimination of the Korean minorities in Japan.

Prisoner / Terrorist

Adachi brings us a film about psychological digression loosely adapted from a text by Auguste Blanqui and no doubt inspired by Adachi’s personal experiences. M., a member of the Japanese Red Army, is the only surviving perpetrator of the suicide operation at the Lod airport in Israel in 1972. He begins to lose his composure during his incarceration.

Violated Angels

A psychologically maladjusted young man is invited by nurses to come to their dormitory and watch a couple making out. It unleaches a murderous rage in the man. An excessive portrait of a society that "has the murderers it deserves", loosely based on true events as they happened in Chicago in 1966.

- 1 of 3

- ››